The Shocking Truth About Your Memory

The Shocking Truth About Your Memory

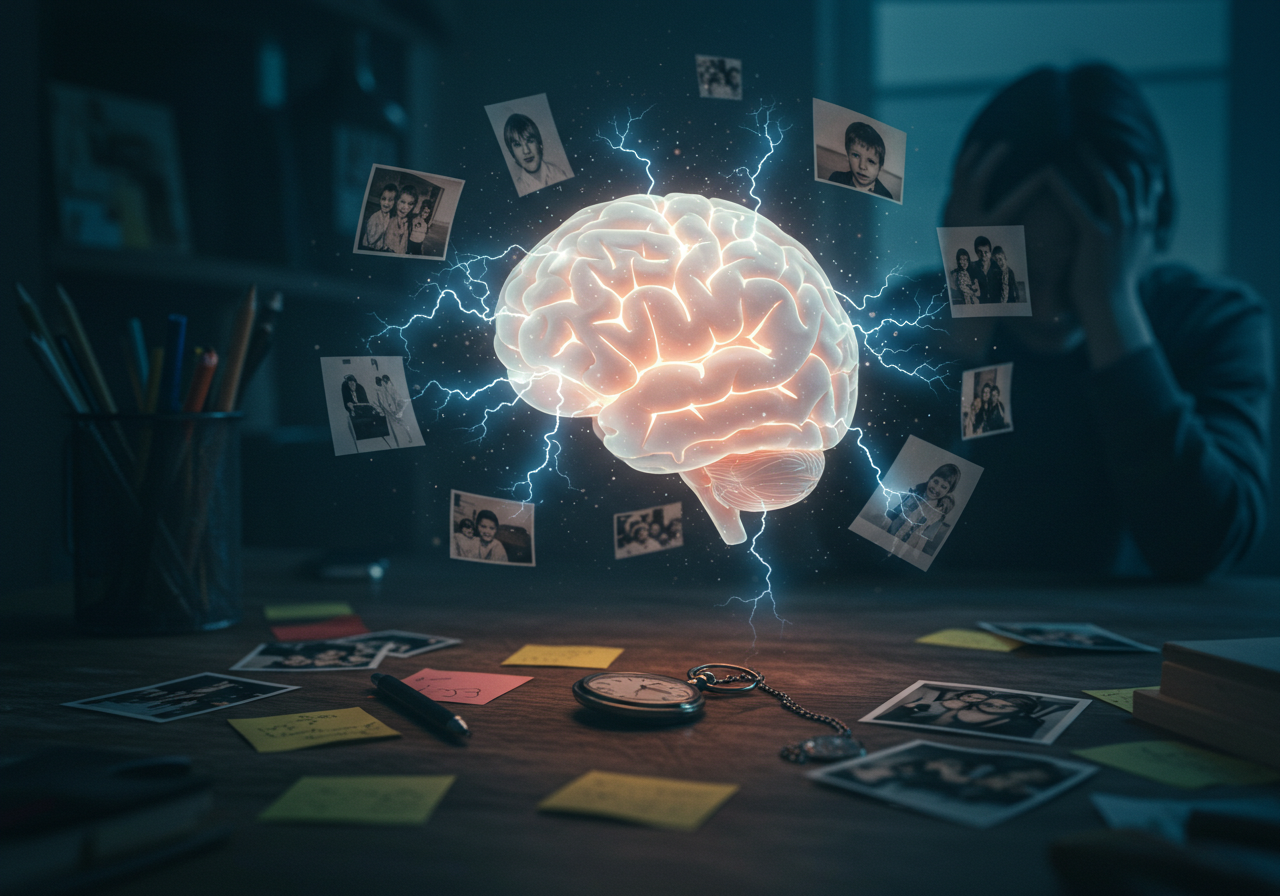

The human memory, often revered as a vast and reliable repository of our experiences, is far more intricate and, surprisingly, fallible than most realize. Forget the romantic notion of a perfect recall; your memory is a dynamic, reconstructive process, constantly evolving and shaped by a multitude of factors. This article delves into the often-hidden realities of how memory functions, exposing the surprising truths that influence what we remember, and more importantly, how we remember it.

The Multi-Store Model: Beyond Simple Storage

For a long time, the prevailing understanding of memory was based on the “Multi-Store Model,” a simplistic view positing three distinct storage units: sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory. While this model provided a basic framework, it doesn’t fully capture the complexities of the memory process. Sensory memory, holding sensory input for a fleeting moment, acts as a preliminary filter. Short-term memory, the “working memory,” holds information we are actively processing, but its capacity is limited (often cited as 7 ± 2 items). Long-term memory, seemingly limitless, is where information is encoded, stored, and retrieved. However, this view is incomplete.

Modern cognitive science recognizes that memory is not simply a passive storage system. Instead, it is a complex interplay of processes, including encoding, storage, consolidation, and retrieval. Encoding involves converting sensory information into a form the brain can process. Storage is the physical and chemical changes within the brain that retain this encoded information. Consolidation is the crucial process of stabilizing memories over time, making them less susceptible to disruption. Retrieval, the final stage, is the act of accessing and bringing back information from storage.

The Fallibility of Encoding: The Foundation of Imperfect Recall

The process of encoding is inherently subjective and susceptible to errors. Attention, a limited cognitive resource, plays a vital role. If we are not paying attention, the information is less likely to be encoded effectively, and therefore, less likely to be remembered. This explains why we often struggle to recall details of seemingly mundane events. Furthermore, our emotional state during encoding significantly impacts memory. Events accompanied by strong emotions, both positive and negative, are often better encoded, leading to more vivid and lasting memories. This is due to the amygdala, a brain region involved in emotional processing, interacting with the hippocampus, the brain’s primary memory center.

Furthermore, our prior knowledge and experiences influence how we encode information. We tend to interpret new information through the lens of our existing schemas – organized knowledge structures that guide our understanding of the world. This can lead to distortions in memory, as we may fill in gaps in information based on our schemas, leading to inaccurate recall.

The Construction of Memories: A Reconstructive Process

Memory is not a perfect recording; it is a reconstruction. When we try to recall an event, we don’t simply replay a pre-recorded video. Instead, we actively reconstruct the memory, piecing together fragments of information and filling in any gaps. This reconstructive nature makes memory vulnerable to errors and biases.

One common error is the “misinformation effect,” where exposure to misleading information after an event can alter our memory of the original event. For example, if you witness a car accident and are later asked leading questions about details you didn’t see, your memory of the accident might be altered. This highlights how easily our memories can be manipulated and shaped by external influences.

Another source of error is the “source monitoring error.” This occurs when we remember the information but misattribute the source. For instance, you might remember a piece of information you learned from a book, but later mistakenly believe you learned it from a conversation. This can lead to significant inaccuracies, particularly in recalling the details of personal experiences.

The Role of Emotion: For Better or Worse

Emotion exerts a powerful influence on memory. As mentioned earlier, emotionally charged events are often remembered more vividly and for longer periods. The amygdala and hippocampus work in tandem during the formation of these memories, strengthening the memory traces. This can be advantageous, enabling us to learn from potentially dangerous or significant experiences.

However, emotional memories are not always accurate. The heightened emotional arousal can sometimes lead to distortions, particularly during retrieval. The “weapon focus effect,” for instance, describes how witnesses to a crime often focus on the weapon used, while paying less attention to other details, such as the perpetrator’s face. This is due to the brain’s prioritization of immediate threats, leading to biased encoding of the event.

Moreover, traumatic memories can be particularly difficult to process and retrieve. The intense emotional response can lead to fragmented memories and, in some cases, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Understanding the impact of emotion on memory is crucial for therapies aimed at treating trauma and improving memory recall.

The Forgetting Curve: The Natural Decay of Memories

The “forgetting curve,” a concept pioneered by Hermann Ebbinghaus, describes the natural decline of memory retention over time. Initially, we forget information rapidly, with a significant percentage of information lost within the first few hours or days. However, the rate of forgetting slows down over time, as memories become more consolidated.

Several factors contribute to forgetting. One is the decay theory, which suggests that memory traces simply fade away over time if they are not actively retrieved or rehearsed. Another is interference theory, which posits that other information interferes with the retrieval of a particular memory. This can happen in two ways: proactive interference (old information interferes with new information) and retroactive interference (new information interferes with old information).

Strategies for improving memory retention include spaced repetition, which involves reviewing information at increasing intervals; elaborative rehearsal, which involves connecting new information to existing knowledge; and mnemonics, which involve using memory aids such as acronyms or visual imagery.

The Future of Memory Research: Bridging the Gap

Contemporary memory research continues to explore the intricate mechanisms of memory. Scientists are using advanced neuroimaging techniques, such as fMRI, to visualize the brain activity during memory formation and retrieval. They are also investigating the role of genes, hormones, and lifestyle factors in memory performance. This ongoing research is paving the way for a deeper understanding of how we learn, remember, and, importantly, how to potentially improve our memory in the future. Furthermore, it holds the promise of developing effective treatments for memory disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, and enhancing cognitive function across the lifespan.

Want to explore more incredible secrets about your brain and memory?

Curious about how far your brain can go? Neuro Surge is the new 2025 formula designed to enhance memory, focus, and mental clarity. Backed by science and optimized for performance, it's one of the top-rated brain supplements this year.

Check this out ➜ 🧠 Boost Your Brain Power Today

📌 Original Content Notice: This article was originally published on Daily Fact Drop – Your Daily Dose of Mind-Blowing Facts. All rights reserved.

Copying, reproducing, or republishing this content without written permission is strictly prohibited. Our editorial team uses factual research and original writing to bring unique curiosities to our readers every day.